Gut microbiome and health – what’s the impact of baked goods?

19 April 2021 | Michael Adams, Head of Product Innovation and Insights and Support Team,

A growing body of research suggests that the vast ecosystem of organisms in our gut plays a much larger role in both our mental and physical health than ever previously imagined. There have even been links found between gut health and COVID-19 severity. Considering that the gut microbiome collectively weighs up to 2kg (heavier than the average brain), it’s easy to see how it is increasingly being treated as an organ in its own right.

Our interest lies in the impact of bakery products on this new ‘organ’; bread being the perfect candidate with its fibre content (acting as a prebiotic) and regular consumption by the general public. This is currently a hot topic, especially with the release of the Superloaf by Modern Baker. Having helped develop it, this new loaf has been designed to optimise gut health with, among other things, a unique blend of fibres.

It’s clear then that this area looks only to grow over the coming years. So, to provide you with some insight, we’ve combined our knowledge of baked goods to explore their role on our gut microbiome, helping you develop products that cater to the consumers interested in these fibre-enhanced goods.

What is meant by gut health?

Gut health is one of the most significant nutrition and health trends within the food and drink industry at the moment. Due to the importance of baked goods within most of the global population’s diets, it is crucial that both the challenges and opportunities this trend presents are understood.

Some of the roles that the gut plays in human health have been known for millennia, however, as research has progressed, it is apparent that the human gut impacts on a huge range of conditions, beyond the conventional digestive health area.

It has also been shown to influence immune system function, psychological health and oncological outcomes. This is also a two-way street, with evidence indicating that a person’s overall health can also have an impact on their gut health. This makes research into this area extremely challenging, as a holistic approach must be taken, understanding the impacts of the innumerable factors across a wide range of conditions.

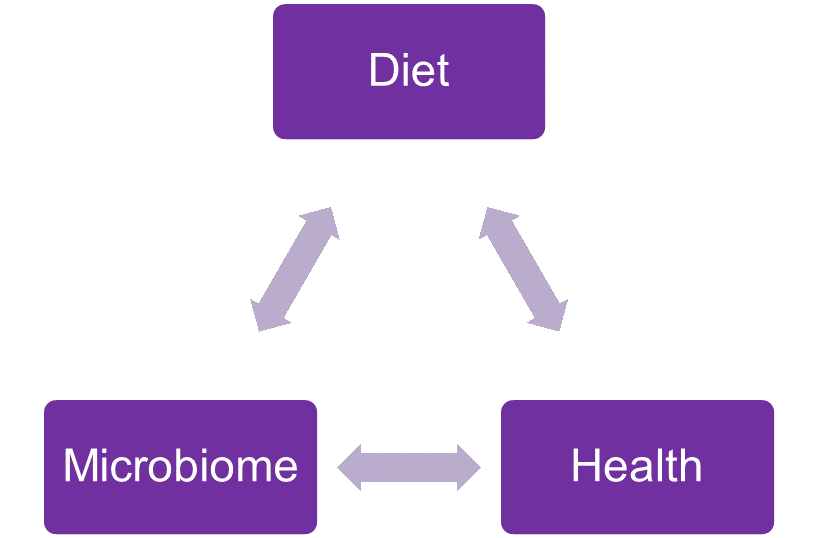

There is little the food industry can do to affect an individual’s overall health over and above their role in developing healthy food products. This is where the link between diet, health and gut health becomes relevant. This is a complex three-dimensional relationship, with each interacting and affecting the other. To further strengthen its importance, research over the past year has found interesting links between gut health and COVID-19 infections.

When discussing the gut, it’s important to understand the different terminology that’s used. The definitions of some of the commonly used terms (bullet-pointed) are often used interchangeably, yet they shouldn’t be since they refer to different aspects of the human gut:

- Microbiome: The collection of bacteria, fungi, viruses and archaea that colonise the digestive tract of humans and the environment. All “damp” places within the body are a microbiome, but the term is used primarily to describe the gut microbiome.

- Microbiota: Refers just to the organisms and not the environment.

- Microflora: Refers to microscopic plants.

- Probiotics: Viable bacteria that, following consumption, colonise the gut. There is some evidence of a positive health effect for acute conditions; evidence seems to suggest that constant consumption of probiotics is required to maintain their levels in the gut.

- Prebiotics: ‘Food for the gut’ to help production of short-chain fatty acids and other fermentation by-products.

One interesting area of research in the food industry is concerning the use of probiotics to modify the gut microbiome. The evidence behind probiotics is mixed, with some of the more recent work showing that whilst probiotics can have a positive effect on gut health, people need to continuously consume probiotics at quite a high level to ensure they continue to colonise the gut. If people stop taking probiotics, the gut reverts to its previous microbiota profile. This indicates that there are significant factors at work that have a direct effect on the microbial population. There is some research showing efficacy of probiotics when used to combat acute conditions affecting the gut, however, evidence showing a sustained impact for chronic conditions or general health is less robust.

The term prebiotic is used to describe compounds that specifically feed the “good” bacteria within the gut. This causes increases in both the number and diversity of species that colonise the microbiome. Prebiotics are generally soluble dietary fibres that transit the digestive system unaffected until they reach the colon where, on arrival, they are fermented by organisms. Significant research is underway to understand the impact of prebiotics, the evidence showing that they are generally of benefit to human health. However, some consumers can experience negative side effects from consuming fibres otherwise known as FODMAPs (Fermentable Oligo-, Di- and Mono-saccharides as well as Polyols), some of which are also prebiotics. Inulin is a perfect example of a FODMAP that can boost a product’s fibre when incorporated which, with the recent push to increase fibre intake, explains the large uptake in our inulin testing in recent years.

The role of fibre in good gut health

One of the most important nutrients for gut health is dietary fibre. It has long been known that its consumption has a close link to digestive health, however, the impact of the different types of fibre and the mechanisms by which they affect the health of the gut is an area currently under investigation. Dietary fibre can be classified by its disparate properties, whether they be physical (solubility, ability to ferment, visco-modifying potential), as well as chemical (degree of polymerisation and base saccharide).

Dietary fibre as a nutrient category is critical and is considered a form of prebiotic. It is well known that consuming fibres can reduce the risk of disease, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer. It is not known exactly how much of this risk reduction is due to the impact on the gut microbiome or other mechanisms, such as the bulking effect cereal bran can have on the stool, reducing transit time. Either way, it is clear that consumers are not eating enough, as shown in Table 1.

| Age group (years) |

Recommendations (g/day) |

Mean intake (g/day) |

|---|---|---|

| 1.5–3 | 15 | 10.3 |

| 4–10 | 20 | 14.0 |

| 11–18 | 25 | 15.3 |

| 19–64 | 30 | 19.0 |

| 65+ | 30 | 17.5 |

| 75+ | 30 | 16.5 |

Table 1: UK fibre intakes (2015 Government guidelines)

...fibres in the bread we consume, particularly wholemeal, can be considered a prebiotic, meaning it feeds our gut microbes improving our gut health.

The role of bakery products

While some effects of bakery products on gut health are well known and understood, such as the role of gluten in coeliac disease (hence the growing need to develop gluten-free products), the wider impact on the human gut microbiome is only beginning to be investigated in detail. Most bakery products are based on wheat flour: a source of fibres. Some of these fibres can be classed as prebiotics, meaning they’re able to pass through the GI tract and stimulate the growth of gut bacteria.

Cereals such as wheat, rye, oats and barley contain many different types of fibres, as shown in Table 2 for wheat.

| Fibre content (g/100 g dry matter) |

Whole‐grain wheat | Refined wheat flour |

|---|---|---|

| Arabinoxylan | 7.1 | 2.1 |

| Cellulose | 1.9 | 0.2 |

| Fructans | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| Lignin | 1.5 | 0 |

| β‐glucan | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| Resistant starch | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Non‐cellulosic residues | 1.9 | 0.9 |

| Total dietary fibre | 14.2 | 4.3 |

Table 2: Different types of fibres found in wheat and flour

Bread, especially wholemeal, is an important source of dietary fibre that is needed to keep our digestive system healthy, help control blood sugar and cholesterol levels; it also makes us feel fuller for longer. All bread, including white, provides fibre that is beneficial to our diet. Wholemeal bread is the highest in fibre, at 7g per 100g, with white bread providing 2.9g of fibre per 100g. The fibre levels in white bread are just below the threshold to qualify as a source of fibre using UK and EU nutrition claim regulatory criteria of more than 3g of fibre per 100g or more than 1.5g of fibre per 100 kcal. There’s also the potential to increase a baked product’s fibre content by incorporating high fibre ingredients, as we found at Campden BRI when we boosted a tortilla’s fibre content by 97% after adding butternut squash skin powder.

However, it is not just the quantity of fibre that makes bread such a beneficial product for the diet, but the range of fibre types from wheat. Cereal fibres possess an almost unique range of fibres among the foods we consume. The rate at which the cereal fibres are digested varies depending on their molecular sizes and structures. Most cereal fibres are classified chemically as carbohydrates (although considered as fibre for EU labelling guidelines), as are sugar and starch. Therefore, bread digestion starts early on with starch conversion to glucose, followed by a sequential digestion of the more complex starches, the fermentation of fructans and the more complex fibres. Cereal constituents will play a role in most parts of the gut.

With this in mind, fibres in the bread we consume, particularly wholemeal, can be considered a prebiotic, meaning it feeds our gut microbes improving our gut health. Better yet, because bread contains a variety of different fibre types, from the smaller soluble molecules through to the larger insoluble bran fibres, there is a range of benefits throughout our gut. This is often the real benefit that comes from fibre in bread and can, in some cases, be considered more important than the quantity of fibres per 100g of product. Overall, we need a range of fibres to promote gut health and it is our daily bread that can help us ensure we consume sufficient quantity.

Looking to develop high fibre products?

Many consumers are looking to increase the fibre in their diet which is why so many businesses are developing products that cater for this need. However, this is no easy task. Developing new food and drink products is a complex process - requiring knowledge of ingredients, processing techniques, packaging materials, legislation and consumer demands and preferences.

From bread, biscuits, cakes and other flour confectionery to pancakes, cereal bars and extruded products, we work closely with clients to provide a tailored service to meet their specific needs, including reformulation to provide 'healthier' alternatives.

Do you need help in this area? Get in touch today and find out what we can do for you.

About Michael Adams

Mike has worked in the food and beverage industry since 2006. Before joining us at Campden BRI in 2016, Mike worked in technical, quality and R&D roles within Mission Foods, PepsiCo, and Holland & Barrett. Mike studied for a BSc (Hons) in Microbiology at the University of Manchester, graduating in 2005.

Mike’s team support various clients, providing innovation services, research and analysis across a wide range of products, using our state-of-the-art laboratories and pilot plant facilities.

Understand baked products better with our baking courses

From baking basics to biscuits and beyond - take a look at the full range of high quality training that’s delivered by our experts to develop and grow your workforce‘s skills and talents.

How can we help you?

If you’d like to find out more about how to optimise your products for consumers interested in fibre-enhanced goods, contact our support team to find out how we can help.

This blog was first published in Baking Europe.