Sensory claims substantiation: an overview

30 January 2020 | Marleen Chambault, Sensory and Consumer Research Scientist and Departmental Statistician and Sarah Thomas, Consumer Insights Manager

This white paper aims to define sensory claims, provide an overview of how they are regulated in the UK and explain how they can be substantiated. This document is not a step-by-step guide for substantiating sensory claims. Its purpose is to discuss the practicalities and possible issues surrounding the sensory claim substantiation process, and provide recommendations based on practical experience.

What is a sensory claim?

A sensory claim is a ‘statement about a product that highlights its advantages, sensory or perceptual attributes, or product changes or differences compared to other products in order to enhance its marketability’ (ASTM International, 2016). Sensory claims feature across all types of advertising media, including print (e.g. product packaging and magazines), TV (e.g. TV ads), radio (e.g. radio ads), online (e.g. manufacturers’ and online shopping websites) and outdoor (e.g. bill boards) media.

Why make a sensory claim?

In markets that are increasingly saturated and often very competitive, sensory claims can be a powerful marketing tool to highlight the unique selling point of a product (Choudhury, 2017). Claims are thought to help consumers shape positive expectations towards a product at the point of purchase (e.g. on-pack claims) or pre-purchase (e.g. claims within TV commercials). Ultimately, their goal is to positively impact on consumers’ purchase decisions. To that end, claims need to be perceived as meaningful, as well as relevant and credible by consumers (Wolf and Margoshes, 2014).

Sometimes sensory claims may be used as alternatives to health or nutrition claims. However, whilst consumer studies have demonstrated the positive impact of health and nutrition claims on product choice and purchase, to date not many studies have measured such an impact from sensory claims.

The different types of sensory claims

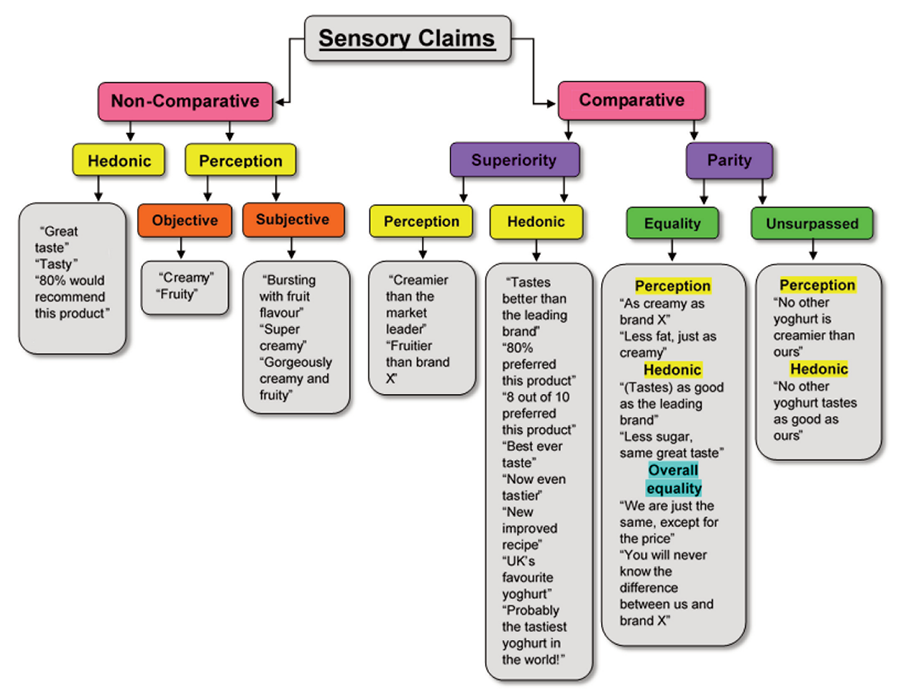

Sensory claims communicate a product’s performance (sometimes in comparison to similar products), improvement (vs. competitor(s) or a previous formulation) or parity with other similar products (Statistics for Industry, 2019). They are categorised into ‘comparative’ and ‘non-comparative’ claims (ASTM International, 2016):

- Comparative claims compare similarities and differences between two or more products (different brands or formulations/recipes within the same brand) and are divided into two categories, namely parity and superiority claims. Both parity and superiority claims have two main areas of application: communicating about overall or attribute-specific liking/preferences (hedonic claim type) or communicating about the intensity of a specific sensory attribute (perception claim type). Superiority claims assert a higher level of performance or liking, whilst parity claims assert equivalent levels of performance or liking (often against a market/category leader). Parity claims are themselves divided into equality claims (products claimed to be equal in one or more features) and unsurpassed claims (existing product(s) no better or higher (in intensity) than the advertiser’s product).

- Non-comparative claims, which are common in new product types, convey something specific about a single product in terms of characteristics, performance or benefits. Whilst objective characteristics such as ‘strong fruity flavour’ are relatively easy to substantiate, more subjective characteristics/benefits of the product or product experience such as ‘delightful fruit flavour’, ‘comforting fruit flavour’ and ‘luxurious taste’ are more difficult to substantiate. Product manufacturers/advertisers often seek to use comparative superiority claims, whilst noncomparative claims can be just as effective (Thomas, 2019), as well as less expensive and easier to substantiate. Non-comparative claims (Corbin et al, 2019) are also less likely to be challenged (particularly by competitors) and remain valid in the event of changes within the product category (e.g. change of market leader; reformulation or withdrawal of certain products, which may have been tested as part of the substantiation process of the comparative claim).

Using a product example (fruit yogurt), Figure 1 provides examples for all the above types of claim.

Figure 1. The different types of sensory claims

The term ‘puffery’ is sometimes used to refer to claims such as ‘as light as a feather’ or ‘luxury never tasted this good’, which are obvious overstatements/exaggerations about a product (Rogers, 2012; Schneider-Häder and Beeren, 2015). Such claims cannot be substantiated but are generally accepted as most consumers would not believe them to be true.

The regulatory framework for sensory claims in the UK

Unlike health and nutrition claims, sensory claims are not subject to detailed statutory regulation, which often makes it easier for product manufacturers/ advertisers to use sensory rather than health or nutrition claims. In the arena of sensory claims, the Consumer Protection from Unfair trading Regulations 2008 is one piece of legislation which prohibits unfair marketing to consumers, including misleading or aggressive advertising (House of Commons Library, 2017). As the law that governs advertising claim substantiation (including sensory claims substantiation) is drawn from a variety of legal practice areas and disciplines (American Bar Association, 2017), obtaining legal advice is recommended (Corbin et al, 2019; Schneider-Häder and Beeren, 2015).

By law, product manufacturers/advertisers are required to have ‘reasonable basis’ for their claims (American Bar Association, 2017). Although there is no requirement to publish the substantiating evidence, there is a requirement to provide the latter for inspection in the event of a complaint. In the most extreme cases, the evidence can even be challenged through a court of law.

The type and amount of evidence required are not linked to the scope of the claims, i.e. whether the claims feature on product packaging or in TV commercials. In all circumstances, not only the claims need to be relevant (performance or benefit claimed to be noticeable by consumers), they also need to be reasonable, i.e. fair, representative and unbiased (Wolf and Margoshes, 2014). Product manufacturers and advertisers have the obligation to ensure that what they communicate about their products, whether implicitly or explicitly, is truthful, not misleading, exaggerated or ambiguous (Ware and Tye, 2014). Competitors, but also consumers, can complain about claims they have seen, which they believe to be e.g. misleading, harmful or offensive.

The different organisations that regulate sensory claims and handle complaints in the UK

Ofcom (Office of Communications) is the regulator for all communication services (including TV, radio and broadband services), whose role includes the public’s protection from harmful or offensive material (Ofcom website). However, it is the ASA (Advertising Standards Authority), the UK’s independent regulator of both broadcast (incl. online, TV and radio materials) and non-broadcast (e.g. prints) advertising across all media, which is responsible for applying the codes of advertising (ASA website).

The codes of advertising, i.e. the CAP and BCAP codes, are written and maintained by members of the advertising industry, which are organised in committees: the Committee of Advertising Practice (or CAP for non-broadcast advertising) and the Broadcast Committee of Advertising Practice (or BCAP for broadcast advertising). To comply with these codes, claims must not be misleading, ambiguous, harmful or offensive, and be verifiable, accurate, decent, honest, fair, etc. (Ware and Tye, 2014). Although each country has its own advertising as well as product labelling laws/rules, these key principles apply in most countries (Statistics for Industry, 2019).

The ASA checks ads across all media for non-compliance with the advertising rules, but also responds to complaints from consumers and businesses, and decides whether ads/claims should be banned or not. Most complaints are generally from members of the public and concern potentially misleading ads (ASA website). The number of complaints does not dictate how likely ads/claims are investigated (one complaint is enough to start an investigation) or banned/’upheld’. The ASA puts an emphasis on ads in sectors where there are potential consumer protection issues, or societal concerns about specific products (e.g. alcohol and e-cigarettes).

The ASA does not ‘clear’ those ads that are shown on television (or the sensory claims within it): this is the role of Clearcast, another non-governmental organisation. Clearcast primarily checks that ads which are to appear on television follow the BCAP code, but also offers a variety of services such as: supporting agencies with creative challenges in restrictive advertising categories, providing appropriate ad timing and scheduling restriction instructions for broadcasters, working with advertisers to defend complaints made to the ASA on ads cleared, helping agencies, creatives, advertisers and broadcasters get to grips with ad rules, offering international (including UK) ad compliance management, and reporting music used in ads (to the PRS) so that artists get paid.

Products and their packaging are generally excluded from the scope of the CAP code. However, when products and their packaging are featured in marketing communications (e.g. in a catalogue or in a product listing from a website), the presentation of the ‘pack shot’ and any claims that are visible fall within the remit of the CAP code. When product packaging features a promotion (e.g. a ‘Buy One Get One Free’ claim), the CAP code also applies to content which relates to that promotion.

Rather than the ASA, Trading Standards is the organisation that consumers can contact (using the citizens advice consumer helpline) to report misleading claims featuring on physical products (including sensory claims). Consumers also tend to contact Trading Standards (Citizens Advice website) if they were sold something unsafe or dangerous (e.g. a food past its use-by date), fake, not as described (e.g. something advertised that wasn’t included in a package deal), or that they didn’t want to buy (e.g. bought under pressure). Trading Standards advise on and enforce laws that govern the way we buy, sell and rent goods and services. Trading Standards acts as ASAs legal ‘backstop’ for non-broadcast advertising. Failure of an advertiser to comply with an ASA ruling could result in them being referred to Trading Standards (by ASA), who then decide whether to investigate and take any enforcement action (ASA website).

The type of evidence required to substantiate sensory claims

Three types of data can typically be used to substantiate sensory claims (ASTM International, 2016; Choudhury, 2017):

- Analytical/Instrumental data: this type of data, which should be obtained from accredited/validated test methods, can be used to substantiate non-comparative (e.g. ‘soft cake’) or comparative (e.g. ‘softer than product X’) perception/attribute-specific claims.

- Sensory data: this type of data, which should be obtained from panellists who are trained and experienced in the test method used (overall difference/discrimination test, attribute difference test or descriptive analysis), provides an objective description of a product or a comparison between several products. Like analytical data, sensory data can be used to substantiate perception claims, which can be non-comparative or comparative (superiority or parity). Sensory data can also be useful to assess or confirm the feasibility of making a claim by providing reassurance that a difference actually exists (to claim superiority) or does not exist (to claim parity) between the samples prior to their evaluation with consumers.

- Consumer data: this type of data is required to substantiate a hedonic claim, a claim that involves subjective perception (a non-comparative claim such as ‘uplifting’ or ‘deliciously smooth’) or liking/preference judgement (superiority or parity comparative claim). Having supporting evidence from consumers makes the claim more (consumer) relevant. To substantiate some comparative superiority claims which are more marketing claims than pure sensory claims (e.g. ‘the nation’s favourite’ and ‘UK’s #1 brand’), consumer data is sometimes combined with sales/market research data (Schneider-Häder and Beeren, 2015).

Note that both analytical and sensory data provide no indication of how consumers may perceive the product(s). For that reason, they are often collected alongside consumer data - even if the claim is related to the perception of a specific attribute, i.e. not related to acceptance or preference. Collecting more than one type of data increases the robustness of the substantiating evidence.

Guidance on data analysis and number of assessors

The data analysis of sensory and consumer data for sensory claims substantiation can be complex and detailed guidance can be difficult to find. The data analysis depends on several factors, including the number of samples tested, the type of task/question used, the distribution of the data and the number of assessors involved in the study.

Most of the guidance provided by the ASTM (ASTM International, 2016) is on the analysis of data obtained from preference questions (side-by-side presentation of two samples). For other types of questions, the usual parametric statistical methods (e.g. ANOVA) are referred to. Both confidence levels of 95% and 99% are used in the statistical tables provided, making it unclear what confidence level is necessary to avoid challenges.

Here is an overview of the guidance available per type of claim:

- Comparative superiority claims: Where a preference test has been used (typically the case when comparing two samples), the ASTM recommends splitting the ‘no preference’ responses (whose percentage should not be too high to make the claim) between the two samples and applying binomial statistics. Tables (from binomial statistics) are provided, which indicate the minimum number of preference judgements required for specific numbers of consumer respondents. There is, however, no advice in the ASTM on a minimum number of respondents as the risk is with the advertiser with such type of claims (it is the advertiser who risks missing the opportunity to make the claim if the number of respondents is too low). For count-based comparative superiority claims specifically (e.g. ‘7 out of 10 preferred A’ or ‘70% of respondents preferred A’), some guidance and statistical tables can be found in Ennis and Rousseau, 2019, as well as Ennis and Ennis, 2012.

- Comparative parity claims: Where paired tests have been used (typically the case when comparing two samples), for equality and unsurpassed types of claim the ASTM provides separate tables with the minimum choice counts required depending on the number of consumer respondents used. Note that comparative parity claims are harder to support than superiority claims: they require more consumer respondents to protect the competitor, but also to provide an advantage to the advertiser. In addition to the ASTM, further guidance and statistical tables can be found in Ennis, 2016.

- Non-comparative claims: Only limited guidance is available, particularly on those claims which use subjective/emotive language. There is no table such as the ones available in the ASTM for comparative claims that indicate the minimum score or percentage that should be obtained in order for the claims to be substantiated. For example, it is not specified how high a product should score on a specific attribute for a claim to be made on that attribute (e.g. ‘creamy’) or how many consumers should agree with a statement for the corresponding claim to be made (e.g. ‘tastes great’). Whilst 70% has been mentioned (Statistics for Industry, 2019) as an ‘acceptable/reasonable’ minimum percentage with consumers (e.g. at least 70% of consumer respondents need to agree that ‘A tastes great’ in order to claim ‘tastes great’ in relation to product A), there seems to be no cut-off point when testing with sensory assessors (e.g. how high does sample B need to score on ‘creamy’ in order for ‘creamy’ to the claimed. At least 70 on average when using a 100-point scale?). When collecting consumer data, it is also unclear how many respondents are required.

Best practices

For information on best practices relating to sensory claims substantiation, the following references can be used: Statistics for Industry, 2019; Corbin et al, 2019; ASTM International, 2016 and Wolf and Margoshes, 2014. A summary of some of the key points are:

- Involvement of all relevant parties: Legal team, marketing team, sensory/consumer team, etc. should be involved early in the design and throughout the sensory substantiation process.

- Explicit statement of the claim: The wording of the claim impacts on the testing protocol and data analysis. Therefore, the claim should always be formulated prior to actual testing. Prior to testing, it is also important to consider all factors that could have an impact on the data collected (e.g. test location) and therefore invalidate the claim.

- Considering a pilot test: If time and budget allow, running a pilot test can help assess the feasibility of making the intended claim and prevent costly, large-scale consumer assessments where the claim cannot be realistically made.

- Technical considerations: There needs to be a clear technical justification for the chosen methodology design (for the claim to be ‘reasonable’), and only validated test methods and measurement scales (e.g. the traditional 9-point hedonic scale for a hedonic claim) should be used.

- The right type of assessors: For the claim to be ‘relevant’, respondents need to be specifically recruited for the study and be representative of the target audience, i.e. category users/consumers (not necessarily brand users but often more than just category buyers).

- Suitable products: Products should be tested at typical consumption age and of a similar format. If prototype samples are used, testing might need to be conducted (e.g. discrimination test for similarity) to demonstrate that commercial and prototype samples are similar. For a comparative claim, competitor products should be carefully selected (key market players to be included).

- The right test location(s): If the claim is intended to be UK representative, there is a need to investigate whether the claim could be invalidated if consumer testing was conducted at only one location (e.g. when significant differences in liking or product usage are proven to exist between geographical regions).

- Getting the numbers right: Having enough consumer respondents is a ‘must’ and getting a second opinion on the data is recommended.

Common pitfalls typically include (Statistics for Industry, 2019; ASTM International, 2016):

- Lack of evidence: Not being able to provide sufficient or suitable evidence to back up the claim (e.g. not having the right type of data).

- Low robustness: Not having enough respondents. There are no clear guidelines as to how many respondents are required for each type of claim, but with consumer data a minimum of 100 is the ‘rule of thumb’ for a robust design (Statistics for Industry, 2019).

- No relevance: Using respondents which are not representative of the target audience (e.g. using consumer respondents that are not product category users) and/or testing under conditions which may not be representative of normal product usage (e.g. testing in CLT conditions may not be appropriate for a claim relating to product functionality).

- No significance: It is not advisable to make a claim based on test results that are not statistically significant. 5% significance level (95% confidence level) is the minimum requirement (Statistics for Industry, 2019).

- Not meaningful: The improvement or superiority claimed might be too small to be detectable by most consumers.

- Extrapolation of the findings beyond the test limits: e.g. claiming that 80% of women found product A better than product B when in fact it was 80% of the female respondents from a specific location/region who found product A better than product B.

- Invalidity: Utilising a claim that is no longer valid. For instance, a comparative claim may no longer be valid after changes within the product category.

Conclusion

This document illustrates the different types of sensory claims and shows how these can be substantiated. It provides a framework from which further considerations can be built. The question of whether (and to what extent) sensory claims impact on consumers’ purchase decisions however remains and is due to be investigated in the next stage of this research project.

About Marleen Chambault

Marleen holds a Food Science Engineer diploma (equivalent to a Master’s Degree) in Agri-food Business and Management (with a strong emphasis on food ingredients, food processing and statistics) from Agrocampus Ouest, Rennes, France.

Before joining Campden BRI, she held several positions in R&D, Research and Sensory (technician, panel leader, data analyst, sensory scientist), through internships and contracts, on several product applications (texturisers for bakery products and confectionery, flavours for chocolate, beverages, nutritional products, savoury and sweet snacks), in several countries (France, Belgium, USA, UK), with some of the largest companies (incl. Cargill, Degussa, Nestle, GSK, Mars and United Biscuits).

Marleen’s main responsibilities at Campden BRI are to provide methodological and statistical expertise for the Consumer and Sensory Sciences department, to plan, manage and execute scientific and technical research and contract work, and to contribute to the development of departmental capabilities.

Since she started Marleen has worked closely with all teams within the Consumer and Sensory Sciences department, particularly with the Sensory Testing Services team to develop and promote new and additional sensory methods/services. For both Sensory Testing Services and Innovation and Insights teams, Marleen is particularly specialised in the data analysis of large datasets using complex multivariate techniques.

Marleen also teaches statistics on some of the modules for the Postgraduate Certificate in Sensory Science, jointly offered by the University of Nottingham and Campden BRI.

About Sarah Thomas

Sarah is an experienced consumer insights practitioner, whose background in qualitative research provides a skill set that is sensitive to understanding the complexities of individuals’ thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. Sarah works closely with clients to fully comprehend their research needs and respond with tailored study designs that deliver solutions to technical challenges and/or inform new product development.

White paper download

Click below to download a copy of this white paper in PDF format

How can we help you?

If you’d like to find out more about sensory claims, contact our support team to find out how we can help.

References

- American Bar Association. (2017) Advertising Claim Substantiation Handbook. Chicago, Illinois: ABA Book Publishing.

- ASA website. [Viewed 27 November 2019]. Available from: https://www.asa.org.uk/

- ASTM International. (2016) Standard Guide for Sensory Claim Substantiation. E1958-16.

- Chadhury, M. (2017) What’s in a claim? How to develop and validate successful sensory claims. Leatherhead Food Research white paper [online]. [Viewed 1 November 2019]. Available from: https://www.leatherheadfood.com/files/2017/03/White-paper-43-Whats-in-a-claim2.0.pdf

- Citizens Advice website. [Viewed 27 November 2019]. Available from: https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/consumer/get-more-help/report-to-trading-standards/

- Corbin, R.M. et al. (2019) Practical Guide to Comparative Advertising: Dare to Compare. Academic Press.

- Ennis, D.M. and Rousseau, B. (2019) Making Count-Based Claims for Sample Data. IFP Technical report, 22 (1).

- Ennis, D.M. (2016) Parity Claims. Reprinted for IFPress (2006), 9 (4) 2,3.

- Ennis, J.M. and Ennis, D.M. (2012) Justifying count-based comparisons. Journal of Sensory Studies, 27, 130-136.

- Food Standards Agency. (2008) Criteria for the use of the terms fresh, pure, natural etc. in food labelling.

- House of Commons Library. (2017) Consumer Protection from unfair Trading Regulation 2008. Briefing Paper [online]. [Viewed 27 November 2019]. Available from: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN04678/SN04678.pdf

- Ofcom website. [Viewed 27 November 2019]. Available from: https://www.ofcom.org.uk

- Rogers, L. (2012) Sensory Claims Substantiation [PowerPoint presentation paper copy].

- Schneider-Häder, B. and Beeren, C. (2015) Sensory Claims – Methodological approach to development and substantiation. DLG-Expert report 15/2015 [online]. [Viewed 24 October 2019]. Available from: https://dlg.org/fileadmin/downloads/food/Expertenwissen/Lebensmittelsensorik/e_2015_15_Expert_report_SensoryClaims.pdf

- Statistics for industry. (2019) Claim Substantiation. How to Design and Analyse Trials to Support Product Claims [Course notes].

- Thomas, S. (2019) Focus group study on consumers’ perception of sensory claim substantiation. I&I technical report. Campden BRI.

- Ware, D. and Tye, J. (2014) The Insider’s Guide to Advertising Regulation [online]. [Viewed 24 October 2019]. Available from: https://www.sensorydimensions.com/files/1214/1623/0664/Insiders_guide_to_the_ASA.pdf

- Wolf, M. and Margoshes, B. (2014) Navigating sensory claim substantiation for advertising [online]. [Viewed 24 October 2019]. Available from: https://www.sensorysociety.org/meetings/2014%20Presentations/W_AdClaims-WolfMargoshes.pdf